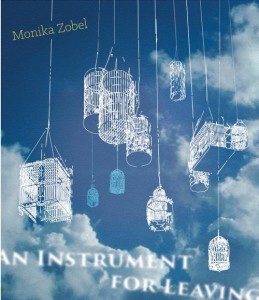

Review: An Instrument for Leaving by Monika Zobel

Reading Instruments: A Fictionista Reports on Monika Zobel’s Poetry Collection An Instrument for Leaving

Lindsay Merbaum

If I read a book and it makes my whole body so cold no fire can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there any other way? -Emily Dickinson

Poetry can make me feel like I’m at a dinner party where I don’t know anyone. I smile awkwardly, unable to think of a thing to say, while my poet friends ooh and ahh. I’m a fiction writer who doesn’t “get” poetry, who can’t make it through a chapbook without falling asleep. But then I come across a preview of Monika Zobel’s An Instrument for Leaving. It is–in a word–electrifying. What is it about Zobel’s work that speaks to me in a way other poets haven’t? I need to find out.

First Reading

I receive a review copy of the book from Slope Editions. I open the package right there in front of the mailboxes, then head up the stairs towards my apartment. Once inside, I flop down on the couch, flip through the pages, inhale slowly, start to read. I read everything–the table of contents, the introduction–without pausing to underline or to make notes. There isn’t even a pen in my hand. I read like this is fiction, turning page after page, taking it all in.

Metaphors are planes at high altitude.

The world

shaken in a curved window.

I wonder if this is the wrong way to read poetry, if you should just read one poem at a time and then sit with it, re-read it once a day for a week, then move on to the next one. But I can’t stop reading.

Train stations appear and disappear

like theatre curtains.

Zobel is socking me over and over in the chest until my heart aches. I’m not pondering what her poems are about, their themes and decode-able messages.

Yes, one could say the sea

makes nothingness blush.

This is a good feeling, the best feeling, the feeling that in your hands is a work of brilliance. The fact that it’s poetry and I haven’t read much poetry since my freshman year of college does not matter. I think of that Emily Dickinson quote my high school English teacher used to paraphrase about good work taking the top of your head off.

Windows invite

the stars for supper.

Second Reading

I make notes, copious notes I’ll barely be able to understand later because of my minute, unstable handwriting that looks like the pen is just leading my hand along behind it, the pen the human and my hand the horse. I might be mixing metaphors but I don’t care. None of this will make it into the review, anyway. I circle words, draw lines connecting them to other words, like a brainstorm or a cloud map. I notice repetition: pigeons, houses, trains, the moon. I recall a teacher in college telling my fiction workshop that her imagery always included boots and eggs, she didn’t know why. I don’t know why. I am reading this book again, only this time I’m going to write about it. I look up Zobel’s references: Georg Trakl, Franz Marc’s painting “The Fate of the Animals,” the artist’s view of humanity forever changed by the horrors of WWI. I translate Schlaflieder–sleeping songs–and Schweigen, which means to keep quiet or shut up. Zobel is drawing me a map and if I follow it, it will lead me to Meaning and Understanding. But I am a poor navigator who reads maps upside down. I long to go back to the first reading, when I wasn’t aware there even was a map to follow. I play cut and paste, piecing together stanzas from different poems in order to tell one story, the story of this book. Then I realize all those stanzas were put in their original places for a reason. I realize Zobel would probably not look too kindly on my scissors. I press “delete,” my bumbling insult to poetry now neutralized.

Third Reading

My deadline is upon me. I am confident that if someone did a poll and asked the general population which produces more anxiety, the end of the world or a deadline, they would all choose the latter because the end is coming someday, but a deadline is happening right now. So, I bake muffins. Then I eat muffins. Then I pace, fiddle with my pen, press “print” and review the four or five pages I’ve got so far, find I’ve written things like:

In An Instrument for Leaving, Zobel addresses the elusive boundaries between place and identity: houses that are not homes, walls that are for seeing, language made of pigeon shit. “I lived two bus stops/from forgiveness,” she writes in “On the Corner of Guilt and Ash,” transforming the intangible into the physical, locating it in actual space.

The cat gets ahold of this page and ecstatically rips it to shreds.

I review my notes. I have underlined the last line of this poem, written a soulful “ohhh” beside it. It ends like this:

At the dinner table, her three children

cling to the life rafts of spoons, observe

their swollen noses in silver mirrors–

how the water rises inside us.

Again, that last line wrecks me. Yes, the water rises inside me. I read more of my notes:

- life lines, leading you away from home

- submerged identity

- the invisible ceiling

- dual identity reference

- immigration–journey of forgetting

- Can your identity be taken from you?

- fleeting thought, a whole story in a memory, a memory in a simple object

- always navigating the roadmap of identity via linguistics, memory

- pigeons again!

My notes look like an existential laundry list. I study the last stanza of “How to Speak of Space.” I’ve found the book’s title in this poem.

Cranes tear the city

apart, one decade

at a time at sunrise.

In the tunnels men in red

overalls roll ache into

their cigarettes.

It’s been said: the boot

is an instrument

for leaving.

The last lines go:

Look into the eye

of a subway, the little

mirrors of motion

There is something happening here that I cannot grasp, something beyond me, beyond what I am able to put into words. I read it again and again, begin to tell a story of a post-apocalyptic world, a city torn down by incessant revision. I realize I am producing a poor translation of the stanza. I haven’t “unpacked” anything in these lines, which are a work of art unto themselves. Here is my crown-less head, the jellied clockwork of my brain exposed. Am I any closer to Meaning and Understanding? Perhaps not. The text is a foreign language, opaque, yet powerful. In it is a gift. I promise myself I will buy any and all books Zobel ever publishes. Then I put my computer aside. My pens can keep it company. I pick up An Instrument for Leaving, sit on my couch with the blinds drawn to keep the sun out of my eyes, and start again, my mind eager for its top to be lopped off once more.

≡≡≡≡≡

Lindsay Merbaum is a fiction writer whose work has appeared in PANK, Epiphany, Anomalous Press, The Collagist, Dzanc Books Best of the Web, and Harpur Palate, among others. Honors and awards include nominations for a storySouth Million Writers Award, a scholarship to Disquiet International Literary Program in Lisbon and the Himan Brown Award for Fiction from Brooklyn College, where she earned her MFA. Lindsay lives in San Francisco with her husband and is currently at work on a novel entitled THE WAILING ROOM.

Monika Zobel’s poetry collection An Instrument for Leaving is available from Slope Editions. Her poems and translations have appeared in Bayou Magazine, Four Way Review, Redivider, DIAGRAM, Beloit Poetry Journal, Mid-American Review, Drunken Boat, Guernica Magazine, and West Branch. She is a Senior Editor at The California Journal of Poetics and the recipient of a Fulbright grant to Austria. Monika currently lives in Bremen, Germany.