Truth is a Sphere: A Conversation with Christina Holzhauser

Christina Holzhauser comes from a speck of a town in Missouri called Portland, a once-popular shipping post located on the banks of the Missouri River. It’s the kind of place where daily events swell to mythic proportions by the time they’re recounted in the local bar the Holzhauser family has owned for close to 80 years. As it is in so many Southern towns, storytelling in Portland is an oral—and fragile—pastime, its tales surviving only as long as they’re remembered, refurbished, and retold. With Portland’s population shrinking, these stories and the sounds that drive them, the individual voices as unique as a musician’s tone, are in danger of being lost.

In her evocative, melancholy essays—two of which have appeared in Rivet’s pages—Christina is keeping them alive, rendering the voices of her family members and neighbors with a fidelity and nuance few writers can sustain for an entire piece. This is experimental nonfiction bursting with heart and sincerity, its craft nearly invisible. By presenting these stories faithfully, without judgment or literary embellishment, Christina is also challenging the power relations that continue to shape them. She doesn’t need to explain the influences working on these characters; it’s all there on the page. As a queer writer loyal to her Southern roots, she is by turns an outsider and an insider. Her essays explore fraught territory from angles that offer fresh perspectives on how we live and work and die and remember. Like postcards, they are brief, personal, and worth saving—if only to catapult you back to your favorite spot along the river, to hear again that voice whose rhythm you had forgotten.

Christina now lives with her partner and their two kids in Columbia, Missouri, where she plays and coaches rugby. In addition to Rivet, her most recent work can be found in the journal Wraparound South and the anthology, Crooked Letter i: Coming out in the South, from NewSouth Books.

I spoke to Christina, through email and over a shared Google doc, about her most recent essay, “Mom Speaks on What Sold at Auction,” the link between anthropology and storytelling, writing in the Southern dialect, and the promises nonfiction makes to its readers, among other topics. The following interview has been edited for grammar and space.

— Craig Dowd, Assistant Editor

Craig Dowd: “Mom Speaks on What Sold at Auction” is your second piece of nonfiction to appear in Rivet. What attracted you to Rivet? I’m also interested in hearing your personal take on what constitutes experimental writing, or “writing that risks,” and why it’s important to you as both a reader and a writer.

Christina Holzhauser I like how Rivet publishes just a few pieces at a time. It really gives the reader a chance to dig in and linger for a while. What caught my eye was the publishing of experimental nonfiction. I feel like that’s not something I see a lot. Writing that risks is anything that feels different to the reader or the writer. While writing both of these pieces, I felt like I was doing something wrong for a long time. I wondered if I could or if “they” would allow it. Having my first piece of risky writing published at Rivet gave me the confidence to see what else I could do.

CD: On the surface, “Mom Speaks on What Sold at Auction” is an inventory of basic household and recreational items, from a cookstove to an accordion, that evoke and represent a wide range of memories and associations for the titular mother. However, while reading your essay, I also felt the influence of power relations at work—gender, class, origins, labor, family—and because of the mother’s immersive and roving voice, a sense of mystery swirls around the auction, the setting, and the individuals involved. Is that a fair assessment? Can you describe the animating circumstances and concerns that inspired you to write this essay?

CH: Growing up, going to someone’s auction was what happened a month or two after a funeral. Being from such a large extended family, and having a close knit community, meant that I went with my parents to a lot of auctions. This particular auction happened when I was nine, after my gramma died. My mom had seven siblings who all got along, but they decided it would be most fair if they had “a sale” so everyone had a chance to get what they wanted. This is one of my first narrative memories; I remember the feeling of cleaning out the house, the setting up of the items, the weather the day it happened. I remember when it ended. I remember how empty I felt, and how, even at that age, I couldn’t stand the idea of strangers driving off with things that belonged to my dead grandparents. As I grew older, I understood that this cultural phenomenon was born of necessity; it was a way to make some money to help with funeral costs. But, it was also a secondary celebration of the person’s life and their family. It’s not just strangers who come to sales, but family friends, whole other families, and neighbors. I wanted to convey the emptiness of what I felt and what I think my mom has been feeling for 30 years.

The dynamite is coming.

CD: Your educational background is in anthropology, and much of your writing seems to focus on ancestry and the language of work. These essays are at once uniquely personal and, it seems, representative of entire communities. Although one could argue that all essays are anthropological in nature, I found myself reading yours through that lens, as if I might draw conclusions about your life, your home, from studying the evidence you’ve excavated for this particular essay. It also made me wonder if writing about these items changed them for you in any way, with your written versions replacing the original memories. Can you talk about the role anthropology plays in your work, if any, and if your essays are part of a larger effort to preserve and illuminate an aspect of American life that is too often misunderstood and misrepresented? Or is your process not so deliberate?

CH: There is a term used in archaeology: total mitigation. This is an excavation that happens when, for example, a new road is being built and there is an important archaeological site “in the way.” Our job is then to dig and document, within an allotted time frame, everything we can before the deadline. We hope to get everything, but sometimes that doesn’t happen. The deadline means they’ll dynamite the site and it will be no more; any artifact left in place will be destroyed. I feel that way about my hometown, my family, and our way of life. I mean, I am the end of the Gen X’ers, and how can it be that my grandparents rode horse- drawn wagons to town, my parents had no running water, and I can make a phone call over a tiny screen and see and hear the person on the other end? I’ve always felt like I’m one of the last to live in such a place (physically and psychologically), so it’s my duty to be a story keeper as well as a storyteller. One of the challenges I face is trying to convey where I’m from in an honest way that explains the complexities of rural Southerness without writing stereotypes or caricatures. While I was growing up, the population of Portland was 150; it has decreased by almost half. The dynamite is coming.

It’s true; writing about my memories changes how I remember. A mosaic piece I wrote about sports, gender, family history, and sexuality is now how I remember those parts of my life. Since I’ve pieced them together for an essay, I now can’t remember just one scene without the rest following. It’s strange. It bothers me because I wonder, then, how memory works at all.

… the truth is a sphere

CD: You grew up in a town with only 85 people. I’m curious to know how this intimacy shaped you as a storyteller, and what it’s like to visit your hometown now, as an adult and published writer.

CH: The one thing to do in Portland is go over to the bar to drink and eat with everyone you know. I should mention this bar has been owned by a Holzhauser for the better part of 100 years, so I grew up playing pool inside and running around the perimeter in the dark with the kids in town. The conversations there start out with simple questions: Is the river rising? Did you get a deer? Did you hear that so-and-so died? What comes from those questions is intimate portraits of everyone. No one has secrets. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I chose nonfiction. I spent my childhood listening to creative retellings of the goings-on of all my family and neighbors. My family, too, is full of amazing storytellers, just like most rural and/or Southern families. I listened to the same stories over and over from the same person, with the same pauses for laughs or groans. In that way, it’s been ensured that I’ll pass on these oral traditions. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve become braver and have started asking others involved in the stories to tell their perspective. That’s how I learned that the truth is a sphere.

I go home at least once a month. My last name is on a sign towering above the bar, so when I walk in, I feel like it’s my realm. Even though I left. Even though my politics are the opposite of most people there. But despite it all, my family and neighbors still talk to me. Maybe because they know I write and they hope their story ends up in print. Maybe in spite of it.

CD: You earned your MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, which is about as far away from the South as you can get. Many writers require distance to finally write about home. Was that the case for you? Can you talk about your experience of studying writing full-time, and how you might advise young writers considering the MFA path?

CH: Fairbanks is a very hard, six-day drive from mid-Missouri. Living there was the first time I’d really lived outside of the South. The landscape is already isolating, and I admit I got homesick. I would have dreams about thunderstorms, summer night noises, huge trees with a million leaves. After such long winters, I yearned to smell soil. And when I finally could in late April, it felt like breathing again. That’s when I first realized how Southern I was. That’s also when I started embracing it, in large part thanks to a friend I made there who was from Enid, Oklahoma. We were different from the others, but very much the same.

It was hard for me to settle into the MFA. I was set on becoming a forensic anthropologist, and was still learning to understand that a person could not only get a degree in creative writing (something I’d done “for fun”) but they could get an advanced, terminal degree. My program was three years and lit-crit heavy, so I did a lot of reading and paper writing as well as workshopping my creative writing. What I loved most about the program was being surrounded by so many writers. Growing up, writing was something I did in secret, and even though my parents encouraged me, I didn’t feel like it was a profession someone chose, or something a person should go to college for. I’m really glad I did it, though. In just a few years I was exposed to all genres, made to read works I’d otherwise never consider, and I was forced to write and make time for writing.

To any young writer out there wondering if they should do it: Do it. For me, the MFA was a way to learn how to write, how not to write, and how others write. It taught me how to read critically. And maybe this part isn’t true for every program, but it gave me an intimate experience with all of my cohorts. Whatever you’re writing, you’re putting parts of yourself out there in a format that can be seen and judged. I learned to trust myself and believe in my writing.

Personal essays can be very personal without being confessional.

CD: When I came across your essay “Mom Speaks” in our submission queue, I read it as a character listening to her mom tell these wandering, divergent anecdotes that in turn brought to life her own parents. The “I” is used sparingly and is often replaced with the collective “we,” and so the essay feels like a firsthand account of three generations of people, their characters and voices captured within the confines of a brief list. If you can, please tell me about your method of narration in general and the narrator’s identity specifically, and how you managed to tell such a layered story in such a small space.

CH: In most of the essays I write, I am the narrator and often a character, too. As a narrator, I try to make myself into a film director whose job isn’t, of course, to direct the actors, but to find the right angles for each scene. I generally try not to editorialize or allow whatever version of myself is the character to become too overbearing. Personal essays can be very personal without being confessional. For this essay, I wanted my mom’s voice and narrative style to be the center of the story, so I was hoping the narrator would serve as a window for the mother’s thoughts. In what I see as almost completely removing Christina from the essay, the reader is the one engaged in the act of listening to the mother speak and making sense of it all.

CD: I often find young essayists writing in just one voice—their own, which is often confessional—forgetting that nonfiction can be just as formally inventive as fiction, if not more so. One of the first things I noticed about your essays is that they employ distinctive voices and varying points of view. The oral quality is always prominent. And I imagine that “Mom Speaks” and the memories it contains could have been explored from myriad angles to tell an entirely different story. How do you decide when to write in dialect, and how do you choose your points of view?

CH: For these pieces, I thought that my parents’ words and types of storytelling that told the story much better than Christina as narrator could. Especially for “Dad Tells Me…” it simply wouldn’t be an interesting essay if I wrote about the many times I’ve heard my dad talk about making sausage and occasionally threw in some dialect. I wanted to capture his way of storytelling since he’s been crafting this piece orally for so many years. “Mom Speaks” was once a 10 page essay about the auction told from my perspective of a pensive 10 year old. There was another essay just about auctions and Christina the narrator and character showing how they are quintessentially Southern and rural. My voice did the subject no justice and it was pretty boring, so I chose my mom’s. Both of my parents grew up within 5 miles of each other, but their dialects are different, and I wanted to capture that as best I could with subjects I’ve heard them speak about time after time. I don’t think I could sustain these dialects, and only their voices, for a much longer essay. If the story needed more than a couple of pages, I think I’d try a new approach.

CD: While your essay never reveals any specific details that anchor it to the South, it does feel quintessentially Southern in its tone, content, construction, and execution. From William Faulkner to Dorothy Allison, there is a rich tradition of Southern literature that employs dialect, or the “Southern Accent.” On the other hand, there are just as many examples of dialect being grossly abused and appropriated. How do you navigate, wrestle with, and subvert the preconceived notions, stigmas, and stereotypes surrounding the South and Southern writing?

CH: Well, I hate to be this girl, but write what you know. I spent the first 18 years of my life in the same house in the same town with the same people, and now the past 12 years pretty close to that place. If there’s anything I know, it’s this one spot by the river. I guess I’ve also fully embraced where I’m from. I spent years trying to pretend I was someone else, that I was some city dweller who loved the nightlife and freeways and sirens blaring by my window at 1 in the morning. I have been that girl. And I have loved that place. But it took a lot of work to accept that I cannot live like that. I try to tell the stories of my home and the people there with love and without judgement, even though there are a million things I hate about living in Missouri. It is a part of me. And maybe the biggest part of me. I guess, in short, my answer is sincerity.

CD: Your two essays published in Rivet, though short and concise, are dense with suggestion and emotion. I especially recall the “Big Barrels” section of “Mom Speaks” taking me on an emotional roller coaster. In just a handful of sentences, you convey the various ways these barrels are used and what they represent, their aspect changing from utilitarian to hazardous to playful and innocent. Yet you seldom offer commentary about these items to help readers gain a footing. This, for me, makes the essay not so much a crafted piece of writing but a word-for-word transcription. Are you conscious of striking a balance between revealing and withholding information during the writing process, of dancing on a knife point, or is that something you address while revising?

CH: My mom grew up very poor on top of a very large hill, far away from other people. She doesn’t like to talk much about her childhood, so I get information about her life in small bits that I have to piece together. Even with pointed questions, it’s still hard to get straight answers. I wanted to mimic that feeling for this essay. I relied a lot on the title to situate the reader in context, but I also wanted my mom’s words and the physical content of the sale to root the reader in setting, or, at least a certain type of place.

Your earlier question asking about power relations of gender, class, origins, labor, and family is a huge compliment because, at least for one person, I’ve accomplished what I set out to do.

When a writer calls their work “nonfiction”

they’ve entered into a pact with the reader.

CD: I’ve recently heard countless people say that fiction, or hybrid work, is no longer as relevant in today’s political climate as it once was, and that we need more and more factual writing that is beyond reproach. So I would like to ask you one of the oldest questions around: For you, as a writer, where does nonfiction end and fiction begin? I’m curious to know if you view nonfiction as a porous form, with room for invention, and why you feel it’s uniquely suited to tell your personal stories.

CH: When a writer calls their work “nonfiction” they’ve entered into a pact with the reader. They are saying, “This happened. This is true.” For me, I take that pact very seriously. I do my best to give the whole story, the details as I remember them, the words as they were spoken. If I can’t remember details exactly, I give the reader a hint that I’m guessing, that I’m maybe describing a feeling instead of a truth. When a reader picks up a piece of fiction, they can know, “This didn’t happen but it could’ve.” When a reader picks up a piece of nonfiction they know that it most certainly happened. Maybe nonfiction strips off all the layers we can hide in while reading fiction. Of course when we read good fiction we become the characters; we feel everything and we grieve when the story is done. But maybe, because we know somewhere inside, they aren’t real, we’re able to step away from that story easier. Maybe nonfiction offers readers a more intimate, and forgive me for using this word, raw experience. I write nonfiction because I want the reader to trust me. And, being an anthropologist, I want to capture everything I can and present it truthfully.

In the era of #MeToo, Black Lives Matter, Latinx, and LGBTQIA rights, I think it is important to tell “real” stories. This helps us to personalize events that maybe others can’t relate to. As a queer person, I have a perspective that can be hard for non-queer people to understand. And though it is not my responsibility to educate, I can only hope that when I speak truths, others listen.

This is a book I would’ve secretly checked out

from the library back in 1997 had it existed.

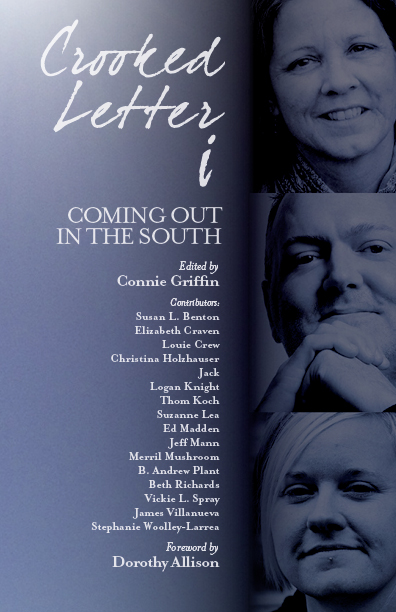

Photo Courtesy of NewSouth Books

CD: You contributed an essay, “The Answers,” to the acclaimed anthology Crooked Letter i: Coming Out in the South, published by NewSouth Books. To my knowledge, Crooked Letter i was the first, or one of the first anthologies of its kind to focus expressly on LGBTQ writers living in the South. Can you tell our readers a little bit about your contribution, how you became involved in the project, and what the experience meant to you?

CH: I got involved simply by submitting an essay to a call for nonfiction about coming out in the South. I was really happy to see Missouri counted as the South because that’s an argument I have with people often. I had an essay called “Bride of the Brides of Christ” which focused on the crushes I had on some Bible school teachers and my confusion about religion and wanting to maybe be a preacher, so I submitted that. It was accepted, but I made some major revisions to detail the actual coming out part and all of its trauma. After Crooked Letter i’s publication, I took part in several book festivals around the South and got to meet the other contributors as well as a lot of readers. It was moving that so many said they’d had the same experience and felt like no one understood, especially how hard it is to deal with a very conservative, very religious town full of family members. This is a book I would’ve secretly checked out from the library back in 1997 had it existed. I hope there are some younger folks out there now, sneaking this anthology off the shelves in order to find someone who can relate to what they’re going through. I would’ve given anything to know I wasn’t alone and that it does get better.

CD: What’s next for you?

CH: I have a few things pending but can’t say for sure when you might see them. I’m also working on an essay about deer hunting and Vietnam, which I’m really excited about. As with most writers, I’m just plugging along and sending things out. In the meantime, you can catch me saying things at christinaholzhauser.com

CD: I’ve been told that you’re a connoisseur of gravy recipes. Care to share any secrets with Rivet’s readers as a parting gift?

CH: No. No, I do not.

CD: Understood. A story keeper can’t give away everything at once! Thanks for your time, Christina.

=====

Christina Holzhauser lives with her partner and their two kids in Columbia, Missouri, where she plays and coaches rugby. She grew up in a town of 85 people on the Missouri River, but ventured out to earn a B.S. in Anthropology from the University of Houston and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. Her most recent work can be found in the journal Wraparound South and the anthology, Crooked Letter i: Coming out in the South.

Craig Dowd is an Assistant Editor at Rivet Journal. Previously, he was a longtime jazz columnist for the triCityNews, an alt-weekly in Asbury Park, New Jersey. He now lives and writes near Philadelphia.