Weird on the Inside: A Conversation with Zach Powers

“Art is a kind of play, and those who forget how to be playful are likely to produce art that is ever more mature and responsible and ponderous.” — Thomas Disch

Zach Powers likes to play—at least when he’s writing. His inventions honor the humble delights of the old pulps, those tales of wonder and whimsy whose garish covers once bloomed on spinner racks in pharmacies across America. A man marries a light bulb. The moon courts a woman. Children defy gravity. But these wacky scenarios—or dumb ideas, as Powers might call them—are trapdoors masking deep pockets of meaning. Watch your step: that story about the devil and his ex-wife might leave you submerged in the kind of bone-chilling pathos typically reserved for stories published in The New Yorker.

Powers creates air-tight vehicles of precision to tell human stories through an absurd lens. I enjoy them for their conceptual audacity and sheer weirdness; but I revisit them for their intellectual depth and finely calibrated prose. If Powers is only playing, he’s playing as Kurt Vonnegut, Italo Calvino, Aimee Bender and other pranksters have taught us to—without rules.

Before joining the staff at Rivet, I read a short story of his titled “When As Children We Acted Memorably” from our print anthology, Writing That Risks: New Work from Beyond the Mainstream. It concerns three children on summer break who discover a portal at the bottom of an above-ground pool that leads to a cabin on a hill. Each time they pass through the portal they visit a different cabin on a different hill. The story confounds expectations by featuring no discernible adventure, no implacable foes, only the inner workings of a friendship. But as fourth grade—and whatever lies outside the cabin—beckons, the three children drift apart, upsetting the balance of the triangle they’d formed. The consequences are strange and profound.

What makes the story memorable is how it creates meaning without employing sentimentality. It’s a seduction. The concept hooks you; the rich sensory details accumulate, drawing you deeper into a new world; and eventually you quit trying to solve the mystery at its core. Understanding the particulars of the portal is no longer important. Maybe it never was. Powers bends a classic fantasy trope into a simple tale that says more about how it feels to grow up, grow old and grow apart than most conventional realist fiction ever does. Like Ray Bradbury and Haruki Murakami, he approaches classic “What if?” literature from a fresh angle, turning oddball entertainment into writing worthy of intellectual consideration.

Although his most notable achievements are in the realm of fiction, the essays Powers occasionally writes are equally impressive. In his first contribution to Rivet, “Putting on Space Suit,” Powers jettisons the fantastical conceits he’s known for and instead looks inward to tell the story of a song, a friend, and an era.

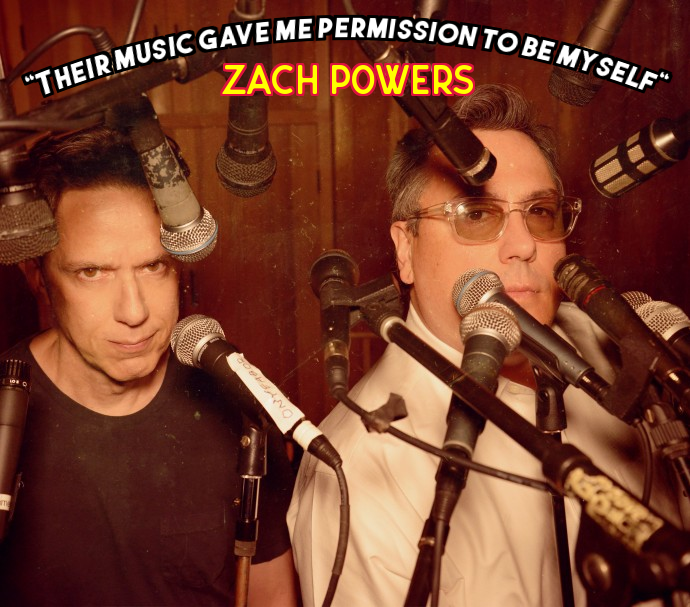

Even if you don’t know the music of They Might Be Giants (TMBG), weren’t alive during the 90s and have never entered a chat room, his essay will remind you of what it’s like to be young and hopeful and a little awkward. Powers writes about those artists and friends who emerge when we need them most, sanctifying the feelings we’re too afraid or unable to articulate, granting us permission to be ourselves. “Putting on Space Suit” is refreshingly different in tone and content from any of the nonfiction we’ve recently published, and warrants rereading.

Powers is the author of Gravity Changes (BOA Editions, 2017), winner of the prestigious BOA Fiction Prize. His debut novel, First Cosmic Velocity (Putnam, 2019), is an ingenious alternate history of the Russian space program during the Cold War inspired, in part, by a real conspiracy theory put forward in the 1960s by an amateur radio operator who claimed to have heard a cosmonaut in orbit who was stranded in space. Writing in Locus, Paul Di Filippo called First Cosmic Velocity “a story of breaking through the veils of identity that stiflingly enwrap us and blinker us, in public and private, and seeing the stars for the very first time.”

Few novels I read in 2019 were as thought provoking and emotionally acute as First Cosmic Velocity. Beautifully rendered and bursting with ideas, my heavily underlined copy now shares a shelf with other counterfactual gems such as The Alteration by Kingsley Amis, The Man in the High Castle by Philip K. Dick, and The Plot Against America by Philip Roth.

In addition to Rivet, Powers’s work has appeared in American Short Fiction, Lit Hub, Tin House, and elsewhere. A native of Savannah, Georgia, he is now the Director of Communications at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and teaches writing at Northern Virginia Community College.

I spoke to Zach through email and over a shared Google doc about “Space Suit,” the enduring appeal of TMBG, the acceptability of wearing dinosaur t-shirts to work, and how studying jazz has influenced his writing, among other topics. The following interview has been edited for grammar and space.

— Craig Dowd, Nonfiction Editor

Craig Dowd: Experimental literature, or “writing that risks,” is a broad and slippery term, but I think the two pieces you’ve published with us begin to suggest its boundless range. They’re distinctly different in form and content yet both are imaginative and daring in their own unique ways. As someone who’s devised his share of strange scenarios, could you talk about the role risk plays in your work and why it’s important to you as a writer and a reader?

Zach Powers: In a way, I find how I write to be the opposite of risky. There’s so much pressure to produce work that fits into a recognizable category, at least if you’re hoping to publish, and we have half a century now of college writing curriculum based largely on the conventions adopted by mid-century realist authors. The biggest risk to myself as a writer would come if I chose to deliberately move away from my natural impulses, which are weird and cartoonish and experimental, at least in terms of narrative. I’m trying to put on paper the way my brain naturally deals with things, and my brain works slantwise and indirectly. Perhaps, then, the risk is revealing to the whole world that I’m all weird on the inside.

CD: In your particular style, often there are absurd elements, such as a man literally painting himself into a corner; fantastical conceits, including secret portals and flying children; and formal gambits, most recently a story told from the perspective of a cardinal. But the writing itself is rarely dense or visually complex. The sentences are smooth and light, shot through with lyricism and humor, and so much fun to read. Is that contrast intentional? Does it make your work more approachable, or digestible, for people accustomed to reading mimetic realism? Meeting a stranger at a party, how would you describe your writing to them?

ZP: I love a good juxtaposition. A weird premise with direct prose creates pockets of meaning in the space where these two elements intersect. When I think about meaning, that’s what I’m thinking of: creating space. The only way meaning can happen is if a reader processes the stuff on the page, and creating unusual pockets gives space for that processing, hopefully in a way they’ve not processed meaning before. That’s the same thing I’m hoping to experience as I write. At a party, though, I usually condense that explanation to “I write weird lit fic.”

I don’t want to geek over my own past. That’s not how I personally move forward creatively.

CD: I picked up First Cosmic Velocity not long after “Putting on Space Suit” arrived in our submission queue, and I was by turns surprised and moved to find a note to Kirk on its Acknowledgments page citing his creativity as a driving force behind your work. I felt as if I knew Kirk, in some small yet essential way, from reading your essay and now here was this connection to your debut novel. Has this piece been gestating for long? Have you ever considered writing about that time of your life from a fictional perspective?

ZP: This piece came together over the course of a few days this past summer. I rarely think about tackling nonfiction—since my prose style is pretty traditional, it’s harder to take risks when I can’t make stuff up—but once I started on this piece and found all the threads that were weaving together, I realized I had an interesting story. I don’t know if I’ll ever write more about this period in my life. Firstly, we already have enough literature about depressed young men. But also, a lot of my thoughts about Kirk can be summed up as “thank you.” I owe him as maybe my greatest creative influence. He introduced me to my favorite author, half my favorite movies, TV shows, you name it. He also taught me to value geekery as part of my creative process. To obsess over something is a way to internalize the things that make you love it, and those things will appear in your own work. But I don’t want to geek over my own past. That’s not how I personally move forward creatively.

CD: On the surface “Putting on Space Suit” is a wistful ode to the relationships you formed in your youth—especially with Kirk—around a deep appreciation of TMBG and its instrumental deep cut, “Space Suit,” and how those relationships played out during the early, uncertain days of the Web. But it also says a lot about how we consume and share and curate art, what it means to discover something seemingly new and innovative on our own, and the various ways we stake out our identities as young people when all we want to do is “feel meaning so badly.” As you conceived the essay, were all of those threads on your mind or did one emerge first?

ZP: I started with nothing but the song. Most of my ideas begin small, insignificant, and often ridiculous. In this case, it all started with a question: Why has this one song felt so strange to me over the years? What is haunting about it? The other threads emerged along the way, and maybe led to the risky aspect of the essay’s construction. I deliberately ignored the impulse to “tighten up” the narrative or focus on one thing. I let myself quest for the in-between spaces, and I kept adding new threads. When I edited the piece, and then working with you, we found the one core storyline, my long-distance friendship with Kirk, but I left all those other storylines more prominent than I might if I was writing a story. I was interested by the way an essay could function differently from one of my short stories. I could give a personal narrative and thoughts on the early internet and an interview and a musical analysis and have it all work together in a forward-moving way.

CD: I can think of several books and albums that punctuate my life or conjure general feelings about certain people and places, and those books and albums are almost frozen in time for me, while my relationships with other works of art are constantly changing and being amended as I’ve grown older. Can you listen to TMBG today without thinking about Kirk and who you were as a young man? Is it difficult or even necessary to separate the personal from the objective when listening to music? I’m interested in hearing your thoughts on this and how it applies to TMBG, because I think it’s connected to your fascination with cultural memory and how some images survive while other details slip away.

ZP: I don’t think of Kirk every time I listen to TMBG, but I do think about him sometimes when I listen. Music conjures memory in the usual sense, which is not a direct input/output. Sometimes the association is triggering and sometimes I’m just listening to a song I like. And while I wrote about specific memories in the essay, sometimes the music makes me long for a general youthful openness. Everything is a discovery as a teenager, and I value that feeling, and I want to experience as an adult writer.

TMBG hold a unique place within my personal musical canon in that they’ve endured more than anything else I listened to in high school. My appreciation for them as a band has actually grown as I’ve developed better critical faculties. They’ve passed the test of my mature scrutiny. So I experience the band both nostalgically and contemporarily. It helps that they’re still going strong today, so I don’t have to just listen to the same songs over and over again. Though as a true geek, I’m of course listening to them over and over.

There’s an audience out there for the unusual. There’s an audience out there that needs the unusual to understand themselves.

CD: TMBG has been influencing young people, especially artists, for decades now. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say their absurd, postmodern ethos can be found in much of your short fiction, as well as in your general approach to writing. In 2019, people are frequently quoting lyrics from “Your Racist Friend,” recorded thirty years ago, as a kind of anthem for today’s current social and political climate, specifically the line: “Can’t shake the devil’s hand and say you’re only kidding.” Can you describe the enduring appeal behind this band’s music and why it continues to find new fans?

ZP: I mention learning lessons from the band in my essay, but maybe the most important lesson TMBG teaches is don’t try to be cool. I think they endure because they never aligned themselves with then-current notions of coolness. Yes, you can hear the 80s in their early albums, but then you can definitely also here not-the-80s. There’s a brilliant book on their album “Flood” in the 33 ⅓ series by S. Alexander Reed and Philip Sandifer. One of the main theses in the book is that TMBG has “a supply of creative resources that so overwhelms the demands of creation that songwriting ceases to be about clearly expressing a single idea, and turns into a playground of excess ideas.” I’m not sure the band ever intended this, but it’s what draws generation after generation of geeks to their music. Geeks, as their defining characteristic, possess excessive interest.

I also think TMBG create a sense of community. For me, listening to TMBG was maybe the first time I ever realized I wasn’t alone in my indirect thought processes. Yes, I’ve been greatly influenced by their music, but more importantly their music gave me permission to be myself. There’s an audience out there for the unusual. There’s an audience out there that needs the unusual to understand themselves.

CD: Now that you’re older and today’s Internet has given us access to unlimited information about anything we can imagine, do you still get the same thrill you once did from discovering an old film or talking for hours with a friend about a new, weird band? After all, we no longer visit the Web; it’s our default home, the connection we can’t escape. With so many experts active on social media, it’s impossible to find something that doesn’t already have a cult following. You could argue these ultra-specific experiences have migrated to podcasts and Twitter, but you’re not calling those people up at midnight to quote from a movie you just saw or driving around with them just to listen to a new album. How do you keep your relationship with culture, with the things and places you love and hold sacred, personal and tangible as we enter 2020?

ZP: I think there are new versions of my experiences available for younger generations, but I don’t know that I’ll be able to tap into them. That’s the generation gap, right? My way of experiencing the world has been partly replaced by newer experiences that will never quite make sense to me. And vice versa. How the hell will I explain Space Ghost Coast to Coast to someone under the age of thirty? How will someone under the age of thirty explain the next revolutionary thing to me? And as far as grown-ups go, I’m pretty open to new things. For every loss of the way things were, there’s a way things are that exactly fills the void. I just try to remind myself to be excited for these new experiences, even if the main people experiencing them aren’t me.

I would never want to know too much about a project before I started working on it. Where’s the fun in that?

CD: I’d like to hear more about the craft and intentions behind this essay. It’s packed with associations, connections, and potential digressions. One memory leads to another. You’re sort of just laying it down, finding your way on the page, and it sticks because of your style. You mentioned Hanif Abdurraqib being an influence, and “Putting on Space Suit” certainly resembles the loose, poetic music essays he’s been publishing in places like Pitchfork, Medium, and The Paris Review. On a sentence level, your piece reminded me of the music columns written by singer-songwriter Elizabeth Nelson, also an ardent fan of TMBG, for Oxford American. I always found your short stories to be these thought experiments that wrap up in a relatively small space. The roving approach you employ for this essay seems like a subtle yet significant departure. What’s so attractive to you about this style of essay, and when can we expect to read another one?

ZP: I’ve never been able to write essays because I can’t wrap up reality the same way I can my fictional universes. So discovering this newer (at least new to me), looser essay style made sense in a way that a tight, taut essay style never did. Since I tend to think associatively, I let myself make the associations and trusted my weird-ass brain to sort out the spaghetti that ensued. And I was pleased with the result (as much as one is ever pleased with their own writing).

Though this style doesn’t look like my short fiction, I think the impulse behind the two forms is the same. In short fiction, I usually find two or three threads to twine together, and pull them as taut as possible. But the tightness isn’t the goal. The goal is to see how the threads interact. This essay is a looser rope with maybe a couple more strands making it up, but it’s still about the interaction.

Lastly, I rarely approach my writing with too much intent. I have a vague sense that a topic or concept would be interesting to write about, and then I try to write about it. The act of writing is where I discover the intent of the subject, how the story wants to be told. The wand chooses the wizard, Harry. Though I don’t think there’s anything magical about it. It’s just my brain figuring out the most interesting way to think about something or to tell a story. However, the brain creates things based in part on what it takes in. So I’ve deliberately given it a concept, and writing is how it sorts out that input into something interesting. I’m an exploratory writer. Even with novels there’s minimal outlining. I would never want to know too much about a project before I started working on it. Where’s the fun in that?

CD: Speaking of craft and form, this might be a good time to talk about jazz and comic books. You earned a degree in jazz studies and co-wrote an excellent scholarly paper on the connections between jazz improvisation and the multiframe interactivity generated among comic book panels. Comic books, of course, are intimately linked to the science fiction and alternate history genres. And one of your influences, Haruki Marukami, has noted the profound effect music has had on his writing. Do you consciously apply what you’ve learned from these mediums to your own work? I can certainly find elements of both in First Cosmic Velocity, whether it’s the deliberate interplay between scenes, the use of theme and variations in language and character, or the steady rhythm of your sentences, like a walking bass line. Is that deliberate or just the byproduct of effective storytelling?

ZP: Uh oh, you’re gonna get me talking about rhythm. I think the way we usually talk about rhythm in writing—even in poetry—can be simplistic when compared to how rhythm works in music. For example, in a lot of contemporary jazz, the melodic lines are incredibly complicated. Take guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel’s early album Enemies of Energy. There’s a steady beat in the background of his compositions, and the melody maintains a musical forward flow, but it’s not a catchy jazz standard like “Autumn Leaves” or “How High the Moon.” This isn’t limited to contemporary jazz, of course. Bebop did it, as well as 20th century classical composers.

What I hear when I write a line, then, is a longer musical phrase that’s occurring over a steady beat. Yes, there’s something like a bass line pacing my sentences, but the words are a melody over that, sometimes defying the beat, running in hemiola or syncopation. Certain words or phrases read faster than others, and certain words read at different paces when placed by other words. One of my default rhythms for a sentence is something like:

Da-daaa, da-da-da d-d-da

Where the final Ds are in a triplet rhythm, ending a sentence with what feels like a quicker pace.

That said, I’m not thinking about any of that consciously as I write. When I go back and revise and read out loud, though, I discover the rhythms my brain was trying to put on the page. I think that’s a byproduct of having studied music. I’m aware of the effect without ever really having to think about it. So all writers should go get a jazz degree, I guess?

Finally, I believe rhythm contributes directly to meaning. You’re manipulating the reader toward a certain effect. Will the melody you write make them linger or hurry them along? What’s emphasized and what’s pushed to the background? When you hear the first notes of a song, you know whether it’s happy or sad before you interpret the lyrics. I recommend to all writers to take a sentence you love and just read its rhythm out loud to yourself. Just use a single syllable. See how it sings, and see how its mood exists independent of its content.

There’s a canon of books published 50 to 100 years ago that are considered “literature” by most readers, while great new works are often ignored.

CD: There are some brilliant genre-defying examples of jazz writing available—I’m thinking of Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful; Rafi Zabhor’s The Bear Comes Home; and my favorite, Nathaniel Mackey’s series of epistolary novels, From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate—but the music is still grossly misrepresented in fiction and often used to evoke an unearned atmosphere of cool and sophistication. Do you have any favorite jazz-related works of art?

ZP: Strangely, I’ve never been especially drawn to jazz as a subject. Sure, I’ll read articles on specific musicians or albums, and jazz photography is it’s own wonderful medium, but I don’t think I could name a novel or story off the top of my head.

The problem of the atmosphere of cool, though, is broader. When most people think of jazz, they’re thinking of a small cross-section of the music, usually from one of several specific eras: swing, bebop, or post-bop. Or they’re thinking of jazz-style vocalists, who are great but aren’t improvising, and improvisation is the defining characteristic of the music. So I guess people want to evoke the idea of a cramped, smoky jazz club in NYC circa 1950 without engaging with the music at its most fundamental level. And there’s nothing wrong with this, really, except that it prevents people from keeping up with the music. Great new jazz is produced every year, but in the minds of many listeners the genre has become frozen in time. Maybe that bothers me most of all because I see the same thing in literature. There’s a canon of books published 50 to 100 years ago that are considered “literature” by most readers, while great new works are often ignored.

CD: For a debut novel, First Cosmic Velocity strikes me as especially bold and audacious from a conceptual standpoint. Most readers equate maiden efforts with autobiography. As an Irish Catholic, you might pen a sprawling, melancholy novel of family secrets inspired by Anne Enright or William Kennedy. You might write a quintessentially Southern story set on Georgia’s Tybee Island, where you grew up. Even Michael Chabon wrote the bildungsroman Mysteries of Pittsburgh before expanding his scope and imagination with The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Klay. But instead you’ve written a surreal alternate history of Russia’s space program during the Cold War on your first attempt. Did you find it intimidating to tackle such a dangerous and secretive period in human history or was the process liberating?

ZP: First, I should admit that there’s an unpublished novel manuscript that came before this one. It’s far from autobiographical—my best friend is not a superhero, for example—but the story does follow a lonely young man, so it comes perhaps from a more personal place.

However, while admitting that almost all novels contain elements of autobiography, I’m rarely drawn to the autobiographical novel, and I don’t think I’d ever be inspired to write one. Instead, I’m inspired to write by subjects that take me further away from myself. I want stories I have to search for. I discover things about myself by exploring subjects separate from me. This is what I mentioned before about creating meaning. Choosing a detached subject is creating a new space within which I can discover something new. On the downside, I’m often guilty of under-privileging my own current worldview versus new ideas. I have to constantly remind myself that just because I’ve had a thought before doesn’t mean it’s not worth sharing. But I still want to learn new things as I write, and I find it hard to learn within the framework of what I already know.

So I didn’t really think of the novel as intimidating. On the contrary, it was much more intimidating writing the “Space Suit” essay because I was putting more of myself on the page.

I don’t wear my dinosaur t-shirts to work, but I do own several of them for weekends.

CD: You’ve had a lifelong fascination with space that was inspired by your older brother, an actual rocket scientist, and you belong to several space exploration organizations. For most of us, though, childhood interests degrade over time, which explains the shortage of dinosaur novels. Tell me a little more about what really started this fascination. How does one transition from devouring books about space to rewriting its history? Did having published a well-regarded collection of unconventional stories give you the confidence to tackle such a loaded subject?

ZP: I think a lot about the nature of adulthood and how so much of what we consider “mature” is a form of posturing. There are adult-shaped holes in society and we contort ourselves into adult-shaped pegs to fit into them. Some of this is a necessary, practical concern in capitalist America: you need income to raise a family and most employers scoff at dinosaur-themed t-shirts in the workplace. But then I think we take a leap of bad logic, conflating “practical” with “proper.” I will adopt practical measures to not get fired, but that has nothing to do with propriety. Much of daily life is going through the motions in a way that preserves our positions in polite society. So I don’t wear my dinosaur t-shirts to work, but I do own several of them for weekends.

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve looked backward to the things that brought me joy or triggered my curiosity in the past. This relates to the theme of geeking I address in the essay. It’s much harder now for me as an adult to find those moments of immersive interest in a subject. For example, I don’t love as many movies with as much abandon as I used to. So I have to believe there was real value in those moments when I had them as a child and as a young adult. And I rediscover that value when I return to such moments.

Researching my novel, I spent about six months reading and taking notes. This was a much more deliberate process than my youthful interests, and it was focused specifically on the Soviet space program, where I didn’t have as much knowledge to begin with. While it was deliberate, it was also an organic process, growing out of natural curiosity. Turning from research to writing ended up being a single, unplanned step. One day I sat down and felt like putting the first words on the page. I’d been excited to learn more about my subject, and then one day I was excited to try to say something new about it. I never gave the rewriting history part much thought until I finished a draft and started revising.

Finally, as a writer of weird stories, the novel almost feels simple. Yes, there’s a high concept, but it mainly provides a framework. The rest of the novel is storytelling, language, and characters that face personal stakes. I tend to write cinematically, so it’s players on a stage. The stage just happens to be a version of the Soviet space program that I made up.

CD: The characters in First Cosmic Velocity have to navigate a culture of lies, manufactured news, and the threat of foreign intervention. So much of Leonid’s daily life is consumed by performance, a solitude and loneliness that’s slightly different from what his twin might experience stuck in space. He’s been “depersonalized” as Norman Mailer said of the Apollo astronauts, yet you’ve provided him with a rich interior life. Are readers interpreting your novel as an allegory of our current political and social climate? Is it possible to keep politics out of your art (or the discussion surrounding it) in 2019? And what do you hope readers will take away from First Cosmic Velocity?

ZP: When I started this project, there was no way I could have predicted current politics. I just happened to write about authoritarian media tactics shortly before we started to see them arise within Western democracies. I’ve had a few readers ask about this, so I do think people are finding resonance between the historical setting of the novel and the present day. However, that wasn’t necessarily a goal I had while writing. In general, I want my work to be revealing about the human condition, at least that’s what I’m hoping to learn about as I write. Maybe the thing I want readers to take away is the idea that we can remain human even in dehumanizing times.

. . . there’s not one path to becoming a writer. I think literature benefits the more unique paths there are

CD: Instead of enrolling in an MFA program directly after college, you held a handful of jobs. I believe you started producing short fiction during coffee breaks from your job in the marketing department at a television station in Savannah. Are you glad you took your time in developing your craft? I’ve heard many writers idealize the nascent years of their writing life, a time defined by no expectations, a freedom to discover, and a willingness to test out every idea, no matter how weird or subversive. How has writing changed for you since then?

ZP: It’s so much fun being free to try dumb shit. It’s fun to fail to understand the broader implications of publishing work. It’s fun to be innocent. But one of the calls of literature is to become less dumb. Both reading and writing literature are educational processes. If you’re not learning and rethinking and revising—not just your work but your whole worldview—then you’re failing. Part of learning, though, is learning what to keep. I still value experimentation and dumb ideas. Hell, I value dumb ideas more than anything else as a writer. The dumber the idea the better. I wrote a whole novel inspired by the two words “space twins” for chrissake. So I was lucky to come to literature from a place of ignorance. It let my natural values take root before they could be influenced too much by external sources. If I’d studied English as an undergrad and gone straight into an MFA program, I don’t know that I would have retained my love of dumb shit. I like to think that I’m enough of an individual that my writing style would have developed no matter what, but I also see how every little thing I’ve experienced has changed me as a writer. I hope most of all that aspiring writers realize there’s not one path to becoming a writer. I think literature benefits the more unique paths there are.

CD: You seem like a model literary citizen, an example of how to participate in the larger literary community. You’re transparent about the writing life, trumpet the authors you love, and talk to literary journals like us. You co-founded the nonprofit Seersucker Live, which promotes the local literary community through reading performances and workshops, featuring national, regional, and local writers. Seersucker actually presented the East Coast launch of our first book, Writing That Risks. In addition, you led the writing workshops at the Flannery O’Connor House for eight years and have actively promoted and helped cultivate literacy in young people. What’s so rewarding about helping writers as they’re just starting out? Does it ever feel like work? And how can people who live in towns where there are no live readings or independent bookstores pitch in?

ZP: It absolutely is work. I say that not to trumpet my own efforts, but to encourage other writers to take note of the people who are doing the work to build local and national literary communities. Just here in D.C. I see so many literary superheroes: Hannah Grieco running Readings on the Pike, Kris King with MoonLit, Rachel Coonce and Courtney Sexton with The Inner Loop, and a bunch of the editors and volunteers behind Barrelhouse.

I think we all do it because we value people who want to write. Before I was an organizer, I was a kid who felt accepted by a community. I found friends and mentors, and I want other writers to be able to find the same. I mentioned liking dumb ideas, but I also like simple ones. Literary community can be as simple as wanting like-minded friends.

For people in towns without existing literary community, I first suggest trying to start one. That’s what we did in Savannah. That’s what several of the people I mentioned here in D.C. have done. It’s important to note that there’s a difference between living in a place with other writers and living in a place with literary community. Writing is a solitary act, and there are a lot of us writers who are naturally introverts. In my experience, community is never something that just happens. It takes a few people willing to do the work of bringing writers together. If you happen to be remote from other writers, then look online. Publish in online journals. Read online journals. Share work you like from online journals. Take an online workshop. If you have the means, travel to an in-person workshop or conference. It takes work not just to foster literary community but to be part of one, too. Hopefully, you’ll like the work of community as much as the work of writing itself.

. . . find a way to claim your writing time and protect it

CD: You’re currently living in Virginia and working as the Communications Manager at The Writers Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Can you talk about what role the Center plays in the community, your position there, and how you transition from writing all day at work to composing work for yourself? I know some people with writing-intensive jobs struggle to feel creative when they finally get to their desks after work.

ZP: The Writer’s Center is among the oldest literary nonprofits in America, supporting writers for nearly half a century. I look at my job as being the person who keeps the Center connected to the broader D.C. literary community. I want more people to take advantage of our services, from workshops to readings to writing space. Basically, I want to make sure the Center is just that—at the center of things. So I get to do cool stuff like attend readings and promote local authors and convince people they have what it takes to try this thing called writing.

As for my own writing, I do that before work. I have to be stingy with my writing time and value it more than the time I’ll spend in my day job. Sorry, boss! I need to keep the responsibilities of life from getting in the way of what I value most. That’s not a skill specific to writers, but the successful writers I know have mastered some form of it. So I get to the Center in the morning and go downstairs to our writing room, and I work for about ninety minutes before the Center opens. And then sometimes I’ll work on a second project in the evening, though I’m usually burnt out by the time I get back home. So if you have a job or family or whatever other obligation, I guess my suggestion would be to find a way to claim your writing time and protect it, even if it’s only half an hour at lunch. Because I’ve seen so many great writers who never found enough time at the desk to complete a project. And contrary to one popular claim, you don’t have to write every day to be a writer. You just have to write when you’re able.

CD: You’re a vocal champion of writing in coffee shops. You even thanked a specific shop on First Cosmic Velocity’s Acknowledgements page. Are you someone who embraces the chaos and noise and interruptions, or do you put on headphones and zone out? If so, what kind of music do you listen to while writing?

ZP: I’m in a coffee shop right now, and until I read this question, I wasn’t even aware of the music being played. When I get into a writing zone, everything else fades out. Maybe this skill comes from years of playing music in noisy clusters of practice rooms. I also let myself be distracted on days I’m distractible. I know I can’t write a thousand words every day. Some days I can’t write any. So I never begrudge myself a chat with a friend. Sadly, my weekday mornings are now spent writing alone. I still have productive sessions, but I also have plenty of days where I feel detached from the world when I finish. I can be up in the morning for hours before I speak a word to another person, and that’s not a feeling I particularly like. I hope one day to return to my coffee shop roots.

CD: Switching gears, I loved “A Poem About Running Over Skateboarders,” which is visceral and electric and kind of hilarious all at once. Have you had any close encounters with skaters recently, and will you write any more poetry?

ZP: My one published poem! I feel like there’s a resurgence in skateboarding, so I do see skaters on the regular. I’m also jealous of them than I never learned the skill. But please, skaters, wear light-colored clothing at night.

CD: What’s next for you?

ZP: I have a couple novels in the works, one of which I was hoping to be further along on now, but I got bogged down, and it might need to sit a while before I can write it. The other is at the very early stages, but I’m hoping it will be a relatively quick first draft. I’m also always working on a story or two, plus a series of craft essays I’d like to one day collect as a book. I’ve felt a little sluggish as a writer since First Cosmic Velocity published, so I’m hoping 2020 gets me back to my usual self.

CD: Thank you, Zach!

=====

Zach Powers is the author of the novel FIRST COSMIC VELOCITY (Putnam, August 2019) and the story collection GRAVITY CHANGES (BOA Editions, 2017). His work has been featured by American Short Fiction, Lit Hub, Tin House, and elsewhere. He is Director of Communications at The Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and teaches writing at Northern Virginia Community College. Get to know him at ZachPowers.com.

Craig Dowd is the Nonfiction Editor of Rivet Journal. Previously, he was a longtime jazz columnist for the triCityNews, his hometown alt-weekly. A Jersey Shore native, he now lives and writes near Philadelphia.